Americans, we’re much better with pop music than history.

Which is why the line in U2’s “Pride” that goes, “Shot rings out in the Memphis sky,” is how a lot of people remember where Martin Luther King, Jr., leader of the American Civil Rights movement, was tragically gunned down in 1968.

That’s because most of us don’t really care where it happened. To most Americans, Memphis conjures up images of the neon lights of Beale Street, smoky barbecue, and dirty blues. In the American collective consciousness of Memphis, the King assassination falls somewhere between Elvis Presley and The First 48.

But not in Memphis. Memphis is the kind of hard-nosed, self-aware city that takes these things personally. Every person you strike up a conversation with in a corner bar, barbecue joint, or blues club will talk to you to no end about “Mim-fuss.” And nearly all will bring up the King assassination and how it changed the city forever.

It is, for lack of a better comparison, Memphis’s 9/11.

Early morning, April 4

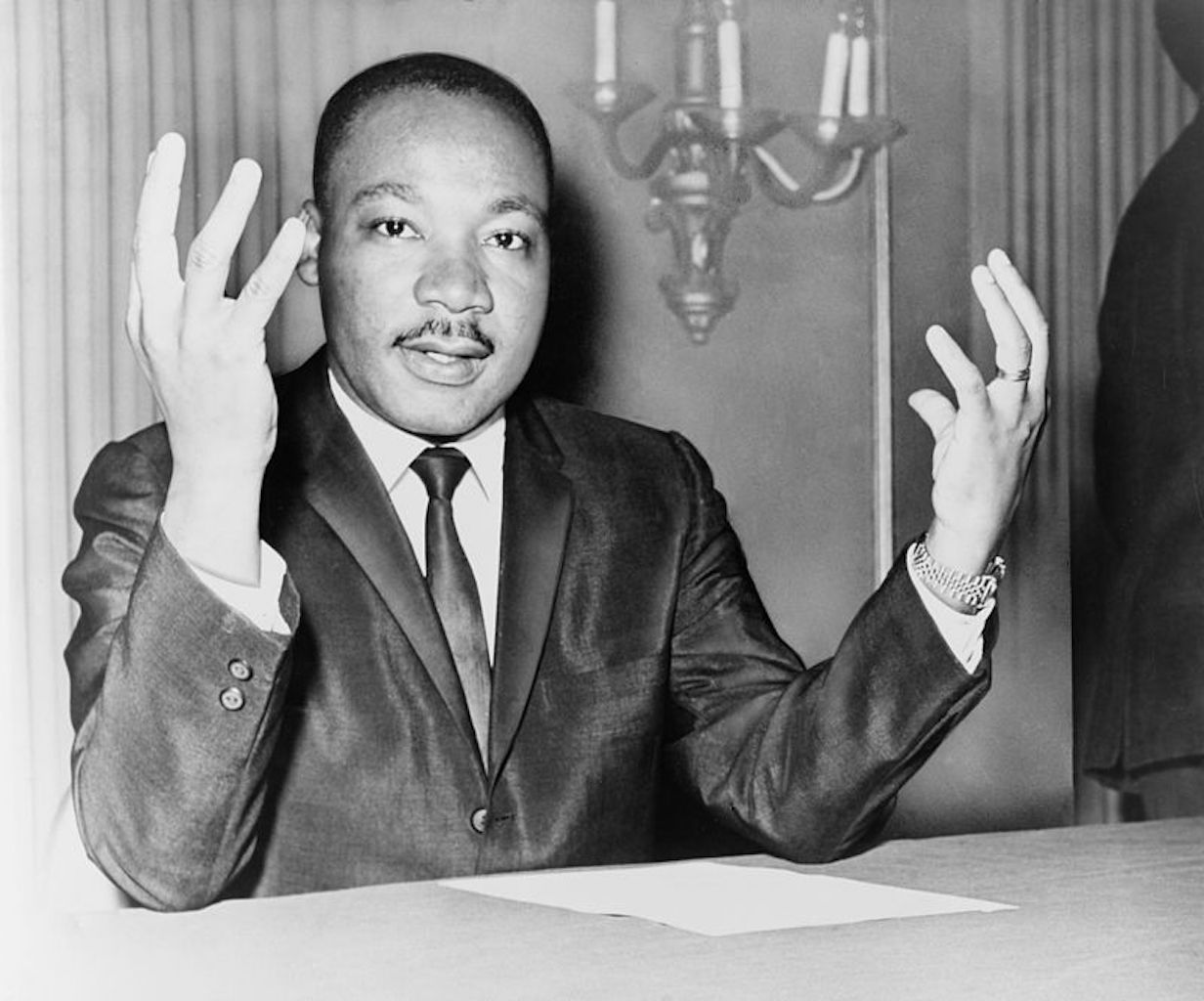

Photo: Dick DeMarsico/Wikimedia Commons

A brief historical review: In April of 1968, Dr. King had come to Memphis to support a group of striking African-American sanitation workers who were protesting their unfair treatment vis-a-vis their white counterparts. It was the beginning of a new phase of the civil rights movement, fighting issues of race, class, and economic inequity. And it was the first instance of King coming to a city to support a movement rather than start it.

On April 4, he stepped outside his room and the Lorraine Motel to get some air and was shot from a warehouse across the street by James Earl Ray.

“Memphians took it very personally,” says Anasa Johnson, Director of the Clayborne Temple, which served as the striking workers’ headquarters in 1968. “How could you not? You think about the greatest leader of the modern age coming to your city because he believes in what you’re doing, and he comes here and is assassinated. One of most devastating moments in modern history, and it happens in your town.”

Though nobody really blamed Memphis, per se, the local community felt it had let the rest of the nation down.

“It’s a very interesting psychology, and it’s difficult to explain,” says Rachel Knox, a lifelong Memphian and the Program Manager for Thriving Arts and Culture at Hyde Foundation, a local arts funding organization. “There’s just that feeling of culpability, that maybe there was some way we could have stopped it, or it could have happened somewhere else.”

The assassination bred more racial tension, undoing much of the work King had done. Riots raged in downtown, crime rose, and almost a decade later downtown Memphis has turned into an abandoned wasteland.

The music industry that had made its home in Memphis, birthing Sun Records, Elvis, B.B. King, and much of early Rock and Roll, fled north to Nashville. The clubs along Beale Street were boarded up and derelict. A place that was once one of America’s great cultural destinations had become the sort of place you didn’t dare get off the highway.

Not that suburban flight was exclusive to Memphis during the latter part of the 20th century. It’s just that as an impoverished and racially tenuous city, the changing demographics coupled with the assassination hit the city especially hard.

“If it’s happening in the country, it’s true two or three times in the South,” says Johnson. “And the music producers and studio owners who left for Nashville, that was all impacted by the sadness and threat of violence and fear that was happening after the assassination. And that’s just one industry; imagine what else left.”

The hollowing out of downtown perpetuated the already depressed Memphian psyche. And like anyone after an intense trauma, the city found it hard to move on.

“Memphis, for the longest time, was frozen in place as a way to protect us from the horrible tragedy that happened,” says Knox. “But one of the things that happens from trying times, it makes your culture flourish.”

A downtown festival shows the world what Memphis has to offer.

Photo: Sean Pavone/Shutterstock

The culture of Memphis is one of grit, plain and simple. It’s a place that’s seen some shit, and they’re proud of it. And it was owning what they were that has allowed Memphis to heal.

“We may not be pretty, but we are the essence of who we are,” says Beverly Robertson, President and CEO of the Memphis Chamber. One thing you can never accuse Memphians of being is fake. “We are not a perfect city, but we are a city with a lot of areas of perfection.”

The desire to highlight those areas led a group of local business leaders to start the Memphis in May festival at the bottom of the city’s decline in 1977. The festival combined a blues festival with a barbecue competition along the banks of the Mississippi River in the shadow of historic downtown, effectively showcasing the music, food, nature and architecture the city still did so well.

“We wanted to show the world we had these great assets,” says Robert Griffin, the festival’s Marketing Director. “We wanted something to bring people back to these bluffs over the widest part of the Mississippi River and see all these great historic buildings downtown. Here we are 42 years later, and Beale Street is booming.”

Indeed, 41 years later the festival had a record attendance of 200,000 last year, accounting for $138 million in economic impact. The festival didn’t single-handedly bring the city out of its slump, but it did alert Memphians, and the world, to all the great things the city had. And that pride became infectious.

It spurred a new interest in the beautiful relics the city had, and much like its northern brothers-in-decay Buffalo and Cleveland, the city began to look at its run-down buildings and envision them as an asset.

“Memphis has succeeded in preserving older sites that have character you don’t find in other places,” says Terri Freeman, director of the National Civil Rights Museum, headquartered in the old Lorraine Motel, which was nearly torn town before being transformed in 1991. “We’ve been creative enough to use this space to draw people in for a collective experience. Where someone can take something that looks to be pretty rundown and say, ‘Here’s the vision,’ and see how it impacts the community around it.”

Several other projects have helped turned the city into a model of restoration.

The Clayborne Temple is in the midst of a long-term restoration to return this 19th-century church to its former splendor. It will serve as a community center for the once-blighted area south of downtown Memphis, just blocks from the FedEx forum and the NBA’s Memphis Grizzlies.

Downtown you can get an apartment at the Tennessee Brewery, a marvelous 1890 red brick brewery reminiscent of Guinness in Dublin or Miller in Milwaukee. Or you can stay at the Springhill Suites situated in the Kress Building, a Five and Dime that opened in 1896.

Of course you can hop through the bars and blues clubs along Beale Street, once again booming, stopping at Silky O’Sullivan’s, which was a 24-hour saloon when it was constructed in 1891.

Photo: Crosstown Concourse/Facebook

But perhaps the greatest testament to Memphis’s reinvention is the Crosstown Concourse, a former Sears warehouse and distribution center that’s now what developers call a “vertical village.” It houses the requisite loft-style apartments, yes, but also an artists’ collective, a small business incubator, a health center complete with sprawling gym, and Kimba Musk’s Next Door American Eatery. The old brick façade has been updated but maintains its true Memphian grit, still a little beat up on the outside even though great things are brewing on the inside.

“I’ve seen pictures of downtown prior to the assassination. You saw it was bustling,” says Freeman. “It had department stores, retail, lots of business. There was a movement away from the city, but the city has begun to recover and there’s so much more vibrancy there now.”

That’s been bolstered by the arrival of two huge new downtown anchor tenants — a large support company for Memphis-based FedEx, and Indigo Ag, a bio-medical related food company that located its North American headquarters in Memphis; the starting average salary there is $90,000.

A new generation propels Memphis into the future.

Photo: Sean Pavone/Shutterstock

“You have to look to the people who claim this city as their own but don’t have [the assassination] as part of their personal narrative,” says Clayborne’s Johnson. “People who were not alive 50 years ago, they see the impact and they say, ‘We don’t have to live in this way. We can acknowledge the moment for what it was and hope for more at the same time.’”

The newer, younger Memphis was on display on a misty January night at the High Cotton brewery near Beale Street. An entrepreneurial “mash-up” was taking over the brewery’s taproom, where bright-eyed young entrepreneurs stood at tables explaining their Memphis-based startups to beer-happy attendees.

A young man representing Code Crew touted his business’s plan to teach coding to at-risk and underprivileged youth as a way out of their current situations. An attractive, well-dressed young woman explained her employer Front Door, a flat-rate, streamlined home selling service that will list and sell any home for $3,500. Another man broke down how his company, SweetBio, makes medical devices and treatments using honey. The startups aren’t the usual glut of apps and inventions you never knew you needed. They also seem to be doing some social good.

The event, if nothing else, showed a side of Memphis few ever see: a young, multicultural city full of young people with big ideas — in a city small enough to have them heard and big enough to make them happen.

A city in recovery, not quite yet recovered

Photo: Sean Pavone/Shutterstock

The city, though much improved, still has a long way to go. Memphis still struggles with crime, and though it’s not something you see in tourist areas or would really encounter on a visit, violent crime is still slightly higher here than it was a decade ago.

Though the city has done an exemplary job of preserving and restoring some dilapidated old structures, you’ll still find yourself passing multiple abandoned housing projects while driving from downtown to the Crosstown Concourse. The city is on its way up, but it’s also well aware there’s a lot of work to do. But nobody in Memphis will deny that.

On the 50th anniversary of the MLK assassination last year, a massive crowd assembled outside the National Civil Rights Museum where Dr. King’s motel room sits just as it did the last morning of his life. On a cold, clear Memphis morning, people of all races gathered to pay tribute to the greatest advocate for human rights America ever knew. For one afternoon in April 2018, the eyes of the world were on Memphis, checking back to see how it was faring 50 years later.

The museum’s poet-in-residence Ed Mabry took the stage, reading a poem written to chronicle the black experience in America but ending in words that sounded like a call for the city to keep fighting on its long road back.

“We go now towards the morning light of work,” the poem finished. “Ready to roll up our sleeves and do what needs to be done for all people to succeed. The bell rung is not the end, it’s the signal to clock in, to come out of your corner swinging. To get on your mark, to get yourself set, in the name of peace, justice and faith, today we go, we go, and we go.”

Bono wishes he could write like that. ![]()

More like this: After falling from the brink of a tourism boom, Nicaragua is ready to welcome the world back

The post How the MLK assassination broke Memphis, and why it’s taken decades to crawl back appeared first on Matador Network.